It was my second summer in Chamonix. I’d met up with Alex and Julian, my climbing partners from the previous season, they had driven down from Munich. We had big aspirations that year. The Walker Spur and Peuterey Integral were on the top of our list, both significant objectives. Before those, we’d need to get warmed up for the season, climbing together to get systems and communication dialled back in.

With this in mind, we set out for Contamine Grisolle on Mont Blanc du Tacul. It was a route we’d planned on doing the previous year, but had abandoned due to conditions. Snowfall had covered the trail down from the summit, so we’d picked other objectives.

The climb started once we finished crossing the glacier to the base of Triangle du Tacul, then onto a snow ramp. We were short roping, the three of us tied together with only 6m of rope in total. It makes sense – if anyone was to fall, they wouldn’t gather much speed before the rope came tight, and we’d all stay on the mountain. I was last in the party of three, looking up at some 48 crampon points, 4 ice axes and a quiver of ice screws. Regardless of the speed, I was fully aware that if anyone fell, it was going to hurt a lot.

We simul-climbed the first 300m, arriving at a protected belay under the couloir which formed our true objective. Alex began leading the first pitch, and before long, neither myself nor Julian could see him. Julian was belaying, whereas I was sitting lower on the anchor, enjoying the view and watching other parties traverse the glacier below.

Below, a team who’d started later than us was making impressive speed as they climbed the neve. They arrived below our belay where I greeted them with a cheery “bonjour”. I received one back – not the normal “bonjour” bastardised by an English accent you hear in Chamonix, this one was proper French.

There was yelling from above. Instinctively, I tucked my head in and held my body close to the snow. I expected shards of ice or some light debris to pitter-patter onto the top of my helmet. Instead, a microwave-sized rock bounced over me… just.

Still looking down after greeting our fellow climbers, I watched the rock strike square into the chest of the man I’d just said “bonjour” to. He wasn’t wearing sunglasses – I know this, because I can still see his eyes. The rock had enough speed that it tore him off the mountain, along with his climbing partner, short roped to him with no chance of holding the fall. I watched as a tangle of rope, legs, arms and ice axes bounced down 300m of snow, ice and rock to the glacier below.

There was no time to process the incident or even think about what had just happened. We couldn’t see our climbing partner – he was still on lead. The last thing we’d heard from him was a faint voice calling “rock”. We thought he would be dead, and he thought the same of us. After much yelling, we learned that Alex was okay and had made a belay.

The climb was no longer a day to enjoy but a day to survive. Descent was no longer an option – the rock cleared the descent path pretty well, and we didn’t want to be there if another rock fell. The rest of the day was long. Parties on the glacier below had diverted toward the bodies while the Chamonix Mountain Rescue (PGHM) long-lined one of their officers to us. He took our phone number and gave us instructions on where to file a report that afternoon.

That’s how I remember it, even if that’s not exactly how it happened. The memory of a face I saw for only one brief moment is engrained in my mind.

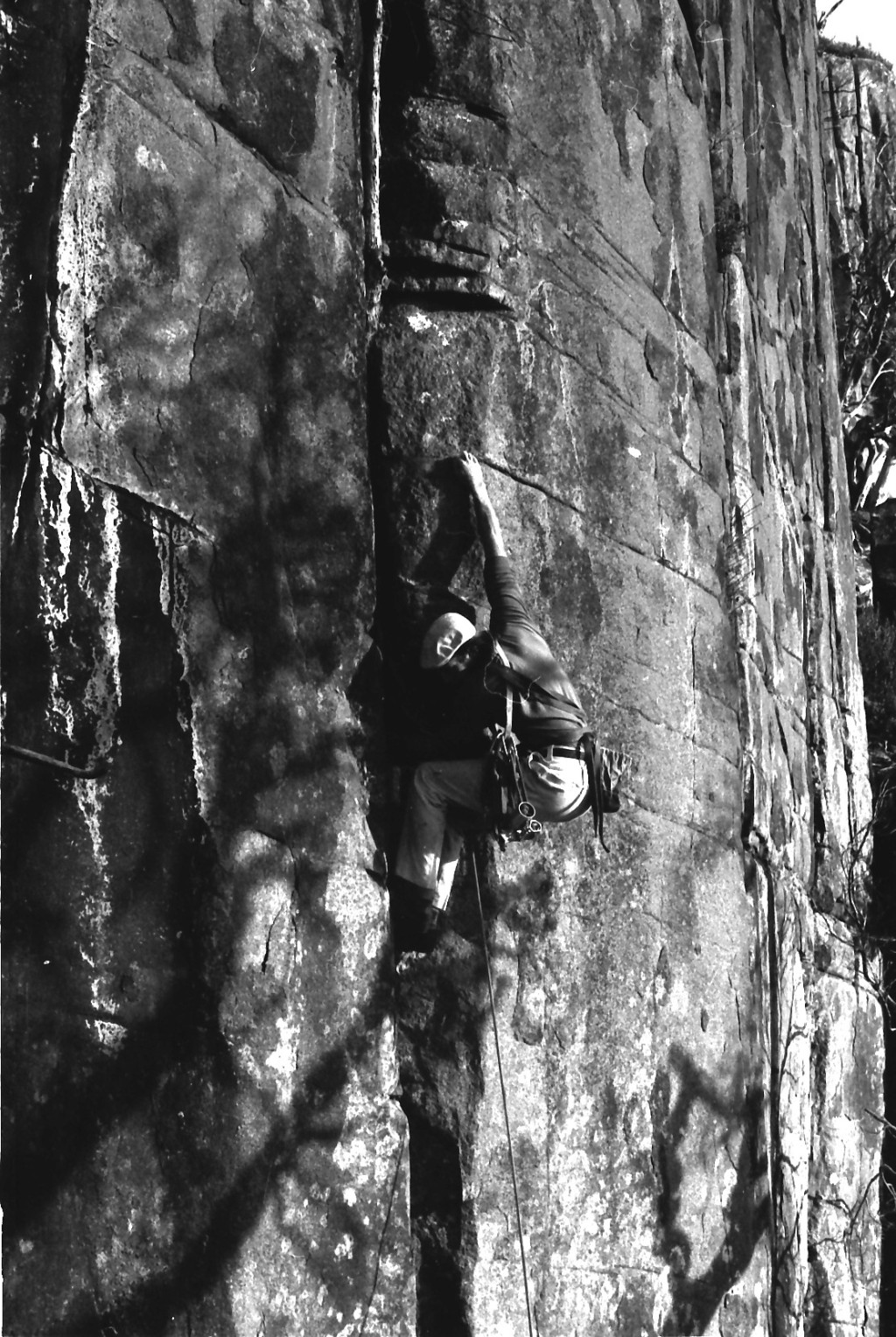

The next day we rested, and then we went climbing again. We didn’t know what else to do, so we continued along as normal. As it began to sink in, I realised I couldn’t stay in Chamonix. No matter what I did, no matter where I went, Tacul was there, reminding me of what I had seen. I posted my alpine gear home and went travelling… well, I rock climbed, but that’s different right?

Going home was the hardest part. I didn’t know how to go back to my job and explain to non-climbers what had happened. I didn’t know how to explain how near of a miss I’d had and that’d it wouldn’t stop me going back into the mountains. Instead, I kept it in. I let it grow. I spent months playing a game called “What If”… What if we had taken five more minutes that morning? What if I hadn’t leaned in when I heard yelling? What if it had been me?

Six months later, I trundled a rock while descending a multipitch sport route. I stood there, momentarily stuck on a ledge, pinned by the fear as I watched the rock bounce down the mountain. I couldn’t share my fear with my climbing partner at the time because I didn’t know how to. So I kept it to myself. Why? He wouldn’t understand, he’s a sport climber who saw near misses in the mountains as badges of honour.

Today, three years on, I was day dreaming of a climbing trip – a big wall of slab with perfect gear. And then the thought of rock fall popped into my mind. I had a little cry and moved on with my day. I’ve learned how to deal with it. I’ve found friendships with other mountaineers. I tell them my story and they listen with compassion. Talking it out is the best thing I ever did.

I have always understood the risks of climbing, and I have tools to respond to them. I have a number of techniques up my sleeve to get myself or my climbing partners off the mountain. I could set up a crevasse rescue blindfolded. I train for these things so if I ever have to use them, I can.

I am aware of my own mortality. It’s something you have to be aware of in an activity with objective danger. I don’t want to die in the mountains, but I understand that objective danger is a part of the sport that can’t be removed. If I die, it’s easy – I don’t have to deal with any consequences. But I don’t think you can be prepared to see someone else die.

I used to be stoic, hiding behind the illusion of everything being just fine. I wanted to be a hard grizzled mountaineer like the rest. The alpinists I’ve looked up to as role models, they’ve all lost partners, friends and family in the mountains. But that’s not a story I ever got to hear. We only see what is on the outside.

Maybe it’s the first time I’ve told you this story, or maybe it’s the tenth. If I’ve told you before, it’s because this is how I deal with it. I share it, because keeping it inside never helped. I’m going to keep on sharing the same story, and if you need to share yours, you should too.

Andrew Banks

Guest Writer

August 2019

Leave a comment